“Leopards love baobabs – there are quite a few giants where one can see leopards resting in. They crawl up to where it is shady and cool. Temperatures in the Makuleke area sometimes reach 48 degrees – so it is just natural to lie on the cooling bark of a baobab.” Haritha Pilapitiya, Trails Guide

The sun has barely climbed the far horizon as it paints the slowly moving fluffy clouds with soft pastel colours. Quietly we walk in single file on ancient paths while the bird orchestra intones its morning master piece. Our route takes us through a breathtaking landscape and past magnificent baobabs.

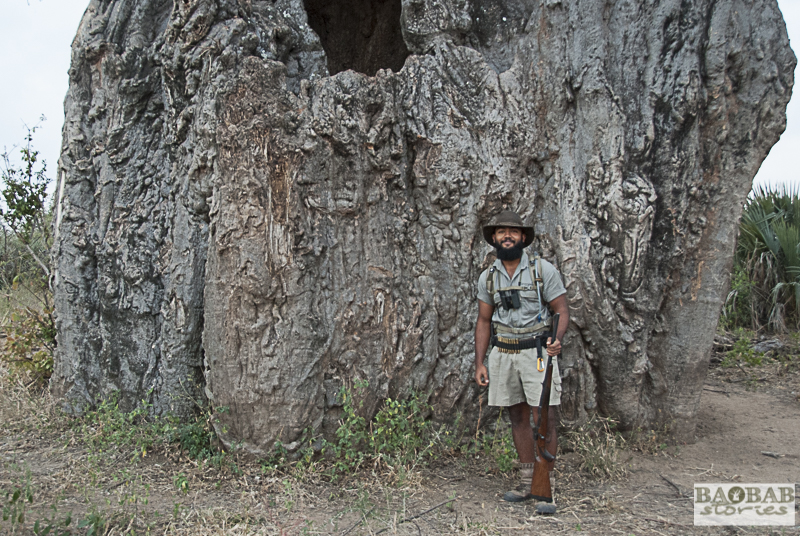

One of the giants looks particularly impressive with its gnarled branches. Naturally, we feel invited to take a break in its vicinity. The bravest of our group try to climb the huge trunk to get up as high as possible. Amongst the “free climbers” is Haritha Pilapitiya, called Hari, who is our Back-up Guide today. Together with Jasper Visser, our lead guide, he makes sure that our walk in the bush allows us encounters with freely roaming animals in this wilderness. We are on foot in the Makuleke Concession in the northern part of Kruger National Park in South Africa where I take part in an EcoQuest course. We are all keen to learn as much about this foreign ecosystem as possible.

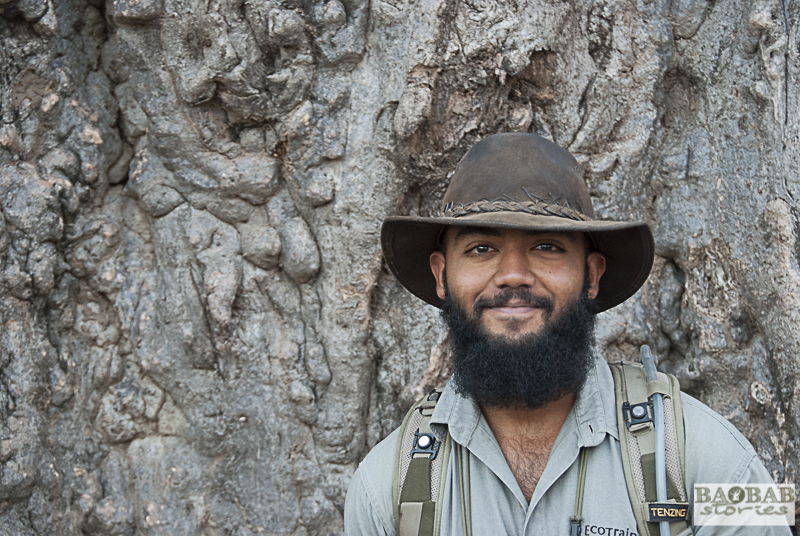

The young field guide carries his weapon proudly and looks quite impressive with it. As I find out quickly he is a rifle handling expert. He originates from Sri Lanka where they “have a lot of animals and large forest areas with great diversity and a single Baobab in the North”, he says. Before he signed up for his courses with EcoTraining he had prepared well for his career as a guide without knowing or intending it: He was on the national team for Sri Lanka and “from the age of 10 to 18 I was involved in professional sport shooting and travelled the world competing for my country up to a point where I could not win any more.” He decided it was time to pick another career.

I wonder what made him choose ‘field guide’ as a profession but it does not take long to understand his move: his father had worked as a lodge manager and in the guiding industry. Some of the camps he managed were in the Yala National Park in Sri Lanka which is famous for the highest density of leopards in the world. Hari got in close contact with the Sri Lankan wilderness where he developed his passion for wildlife from an early age on.

A conversation with a colleague who had successfully finished a Professional Field Guide course with EcoTrianing in South Africa inspired him to sign up for a 55-day Field Guide Level 1 course there. He liked what he saw and enrolled for a yearlong training course. “I was impressed by the standards of guiding and how people in South Africa protect what they have. What I learned affected me in a big way. I saw things that I had never noticed before like little insects and plants that one can talk about to enrich people.” Keen on sports he discovered his passion for walking and topped up his education with a Trails Guide training. “I like walking a lot because it connects me more to nature than exploring it on wheels in a car” he says.

Baobab tradition at Makuleke

While we are on the topic of baobabs Hari mentions an old habitation site of the Makuleke people close to the Limpopo River. People chose places for their settlements nearby prominent water sources. Besides providing water and fish all year long it allowed the settlers to grow crops and to keep livestock. At this specific site a huge baobab grew on a little ridge. It was the tallest point in the area. As Hari heard from colleagues, the chief chose it as his residence, his subjects lived in clay huts nearby.

Baobabs tend to hollow out with age and the one we talk about shows a nice hole with a cavity inside. It served as the entrance to the chief’s home. Pegs drawn into the wood of the trunk helped the inhabitants to climb in and out.

In the 1960s the Makuleke land was absorbed into the Kruger National Park and the people residing in the area were forced to leave by the apartheid regime. After independence the Makuleke people won their land claim and regained ownership in 1998. The chief came back to the land to pay a visit. He was accompanied by guides from the Pafuri Camp. Hari learned from the Pafuri guides that although the landscape had changed the chief recognised the old baobab. Supposedly, he told the people in his company that he had lived in it together with his wife. For the sake of conservation the Makuleke people decided not to move back into the area. Instead they opted to develop it as a refuge for wildlife and plants and rather derive revenues from eco-tourism.

The old baobab is still strong. Since it has not been used for many years the entrance to the cavity has grown tight which makes it difficult to climb in. During his back-up assignments Hare observed that ‘baobab’ seems to be a “big thing in the Makuleke culture because it is like a giant and addresses dominance, power and presence. All the important people sit in the shade of a huge baobab and the others know where to find them.”

The guide has seen many baobabs with natural cavities and apart from using them as living space people stored vegetables and other food items in them. Baobabs store a lot of water in their cells and as a result of that can keep things fresh and cool on hot summer days.

Hyena Encounter under a baobab

One day the guide took a group out on an exciting two nights trail. “I carried a big backpack with food, water, blanket and everything I needed for the sleep out”, he recalls. Nobody carries a tent or other extra weight. People sleep in their sleeping bags and have a breathtaking view of the starry night sky – which actually is part of the fun of a sleep-out and usually much better than a 5-star-hotel. The day was hot and the group did not have much time to cover the distance to the place where they wanted to spend the night. The camp they set up was very basic and showering facilities for the sweaty crowd were not available.

“My backpack got heavy while we were hiking up the ridges” Hari says “and as the sun slowly sunk we set up camp near a former habitation site surrounded with baobabs where Makuleke people lived before they had to leave the area.” The group divided their shifts because somebody always has to keep watch with wild animals on the move so close. The back-up guide was tired and tried to catch as much sleep as possible – he rolled up in his sleeping bag.

But the night started out ‘hectic’: A herd of elephants browsed their way up and through camp. The tired group had to retreat further up the hill. The elephants did not take long to feed in the area with humans around. The group could return to camp where Hari went straight back into his sleeping bag.

“The full moon shone from a clear sky and from where I lay I could see the baobab’s impressive silhouette”, he remembers. The night was cold and all that stuck out from his sleeping bag was his face. Soon, he was fast asleep again. “It was nearly dawn and something was on my left cheek – checking me out with a cold snout – almost like a dog’s but when I sleep I sleep like a log” the adventurer recalls.

The “thing” came up and bumped him in the face again. He ignored it because it could have been bats hitting his face – which he assures me can happen every now and then while one sleeps out in the bush. Finally his nose connected to his brain and he became aware of a horrid smell – a foul smell as that of dead meat. Something started licking his face.

“My face was sweaty and suddenly I sat upright – and with the moon in the back I could see a hyena’s outline”. The guide got his hand out of the sleeping bag and smacked the animal on its head. The creature was not impressed and started coming back. Obviously it was attracted to the salty taste on Hari’s cheeks.

Getting up proved difficult – his right side had fallen asleep on the tough ground and his arm felt numb. He could not grab his rifle. It took him ‘ages’ to climb out of the sleeping bag. Finally he managed and grabbed his torch. A flash at the animal showed that it was only two meters away.

“I looked to the fire place and saw the two people doing their night shift facing the other way. I yelled at them ‘guys, there is a hyena here’. They were shocked because the hyena had snuck up quietly and they did not hear it”, he remembers. All efforts to chase it away seemed to fail – the hyena kept coming back. At some point it stood at some distance and stared at Hari for five minutes which to him felt like an hour. Suddenly it started to descend the Kopjie (hill), went down the ridge, gave a little howl and disappeared into the dark.

Hari could have lost his face or life during this very close encounter. Instead of making a big deal out of it he went straight back into his sleeping bag although he admits that at first he was scared. Looking back it “was a great adventure” he says and laughs.

Future as a guide ahead

Meanwhile Hari is a fully qualified field guide ready to use his skills in Sri Lanka where he plans to introduce walking safaris. He feels sorry that many of the people in his home country do not seem to appreciate the natural habitat which disappears at a frightening rate. But the young guide has a strong vision: “I want to protect our nature with its rich history dating back to Buddha and conserve it for the future. There is still a lot to be discovered. I am keen to walk those ancient forests, discover new places and maybe even new animals.”